Saturday, July 22nd at the Weiser Train Depot a presentation was given on the Weiser Labor Camp from 1943 to 2003. A brief history of the camp, its locations and daily routines was given. Music was performed to help illustrate the time period by musicians, Juan Manuel Barco, Bonifacio “Bodie” Dominguez, Ana Maria Schachtell and Angel Bustos.

Check out the video of the presentation in its entirety on Living In The News.com’s Facebook page.

The following is a brief history of the Weiser Labor Camp provided to those in attendance. Text is by Kathleen Rubinow Hodges and Ana Maria Nevarez Schachtell.

Beginnings

The city of Weiser lies where the Snake and Weiser Rivers join along the Oregon-Idaho border, and has always been surrounded by farms. For 60 years, the Weiser Labor Camp housed many of the farmworkers who helped to grow the crops.

From the 1940s through the 1990s nearly every small town in southern Idaho had its own farmworker housing. In Weiser, the labor camp was owned by a farmers’ group called the Weiser Labor Pool. It sheltered several hundred people most summers from 1943 to 2003.

When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, the country changed overnight. Food was rationed. Sugar-used for cooking on the home front, feeding troops, and in many manufacturing processes including weapons production- was one of the first crops affected. Farmers in Idaho and Oregon were encouraged to increase their output of sugar beets. Other crops as well used hand labor intensively. At various times farmers have grown lettuce and peas on the Weiser Flat; strawberries on the Oregon Slope; and potatoes, corn, and onions.

During the Depression of the 1930s, farmworkers and their families followed crops around the West as harsh economic conditions pushed them out of their homes and communities. Some, though not all, were Mexican or Mexican American. Others were Dust Bowl refugees. Now military recruitment and defense industries swallowed enormous numbers of workers.

Weiser newspapers from 1942 and 1943 were full of stories about farmers desperate to find help with their crops. In 1942, Japanese Americans from the West coast were forced into internment camps (including one at Minidoka, Idaho) or worked on farms in the Western Treasure Valley. The United States began negotiating with the Mexican government and the following year reached an agreement, known as the Bracero Program, whereby Mexico would do its part for the Allied war effort by providing farmworkers to the U.S. By 1943, the Bracero program was in place. Workers were recruited in Central and Northern Mexico and traveled north by train to various places including Weiser. In April, construction began on the Weiser Labor Camp.

Locations

The first camp, built in 1943, consisted of tents erected on wooden platforms. It had 20 barracks buildings with stoves and beds, a mess hall, shower room, laundry room, and kitchen. Five Japanese American men were the first residents, joined on June 14 by 48 Mexican nationals, workers with the Bracero Program. Most of the men spoke only Spanish. The workers were sponsored by a group of 20 farmers. The federal government paid some costs for the camp, plus train fare from Mexico. Other farm workers were living on individual farms in the area. In early July a big harvest crew of 300, including Mexicans, Japanese, local women and children, and college students, all worked together to pick an early maturing crop of peas.

A Relationship With Ups and Downs

In those early years Mexican workers were a surprise in Weiser, and curious local residents made genuine, if slightly odd, efforts to welcome the workers in their midst. In August 1943, “both the Mexican and Japanese camps” participated in a community festival, and on September 16, Weiserites provided a Mexican Independence Day celebration that was modeled completely on American norms: fried chicken, cake and ice cream, watermelons, softball, and a performance by the high school band. In the evening, the Mexican workers, either touched by the Americans’ efforts or fed up and homesick, began singing in Spanish. On November 22, at the end of the potato and beet harvests, the braceros boarded a special train and headed back to their homes in Mexico.

The next year, 1944, a co-op of farmers officially incorporated as the Weiser Labor Pool to manage the camp. A Spanish class was offered for local farmers, but there were limits to international good will: the workers went on a brief strike in June, asking for an hourly wage of 60 cents instead of a piece rate, which they didn’t get. Two “ring leaders” were removed from the camp. The men kept busy, working steadily in haying, pea harvesting, and hoeing corn and beets, and also fighting forest fires. In August, because of discrimination at two local businesses, some of the workers requested a return to Mexico. Worried farmers passed a resolution asking local businesses to extend equal treatment to all. There was another brief strike. September 16 brought another multicultural party, this time with soccer and a Mexican movie. Again in 1948, seven businesses refused services to the workers. So, the relationship between the braceros and the town vacillated.

Mike Heredia, Camp Manager 1945-1978

Miguel “Mike” Heredia was in charge of the camp almost from the beginning. He was born in 1907 in Ecuandureo, Michoacán, came to the United States in 1922, and went to work for the Union Pacific Railroad. By the time he arrived in Weiser, he spoke both English and Spanish and could deal easily with authorities. He was manager until his retirement in 1978, the only camp manager in all of Idaho who was of Mexican descent and who gave a lifetime of work to one camp. At first, he lived in a cabin with the other workers, but in 1954 he married María Guadalupe Rodriguez, they bought a house, settled permanently in Weiser, and raised a daughter, Elizabeth. He was in charge of everything: he translated, and helped people to cash checks and arrange loans. He gave people rides to work or to the store. He walked through the camp in the early morning, calling to everyone to wake up and get ready for the day. He even bailed people out of jail! He was also a labor contractor. He got paid by the farmers to find a certain number of workers, and then paid the truck drivers who brought them from Texas. He kept track of who and how many people would work on a given farm on a particular day. The newspapers regularly quoted his reports on the condition of crops and the number of workers coming and going.

Post War

World War Il ended on August 14, 1945, but the need for farm workers continued. Farmers, once they got used to having large groups of workers show up reliably every spring, were not willing to give up those extra hands. Also, more acreage had been planted during the war, and there was high demand for agricultural products as the U.S. rebuilt in the post-war era. Though the bracero program continued after the war, in 1948 the Mexican government refused to send more workers to Idaho because of the discrimination they faced in local businesses. By that time, it was also becoming too costly to bring workers up from south of the border, once federal wartime subsidies disappeared. But Mexican and Latino workers found their own way north. The federal government no longer subsidized the labor camp. Farmers in the Labor Pool hesitated, and then decided to move the camp off rented property. They bought land a little further from the bridge, on West Main Street north of Ninth. They moved the camp, which still consisted mostly of tents on platforms, and made plans to recruit Tejanos. Weiser’s two newspapers noted that “California Mexican workers,” and “Mexican families from Texas,” would arrive soon.

Families Arrive

People who would be important to Weiser’s story showed up soon from Texas. In 1952, the Fuentes family, originally from Cruillas, Tamaulipas, Mexico began traveling annually between Pharr, Texas, Caldwell, and Weiser. The first few years, they rode in the back of a canvas-covered truck, in the company of other families.

Eventually they were able to buy their own car, though they still traveled in groups. Every year they would go back to their home in Pharr in November, spend Christmas holidays with family in Texas and Mexico, and head back to Idaho in April. In about 1959, they decided to stop migrating. They bought a house in Weiser, because there was always a lot of work and the father had good relationships with farmers here. One of the sons, Humberto Fuentes, who was about ten years old when the family first arrived, would go on later to found the Idaho Migrant Council (now Community Council of Idaho).

The Santos family came from a different border town. The whole family moved first from the very small town of Nava in the state of Coahuila to Piedras Negras, close to the border, and then, when they got their papers in order, to Eagle Rock, Texas. While doing farm work in Eagle Rock, one of the older daughters met a group of young women who had been to Idaho, and the next year she traveled with them to Weiser. In 1953, the entire Santos family followed. Joe “Armando” Santos, the oldest son, in later years would become the labor camp janitor and had many other roles as well. His sister, Julia Santos Flores, later Julia Soliz, was 19 years old when the family arrived. Like the Fuentes, they first traveled in the back of a canvas-covered truck, and also like the Fuentes, they made the trip annually until about 1959. At that point, Julia had married Jess Soliz, and the labor camp had moved one half block to its final location. There was a building that was intended to be a store, and Mike Heredia asked Julia and Jesús if they wanted to run it. The new market was named El Ranchito. Through several variations, first as a grocery store on camp property, and later as a small bar and store in an adjacent house, it was the social center of the camp and surrounding neighborhood for several decades.

Daily Routines

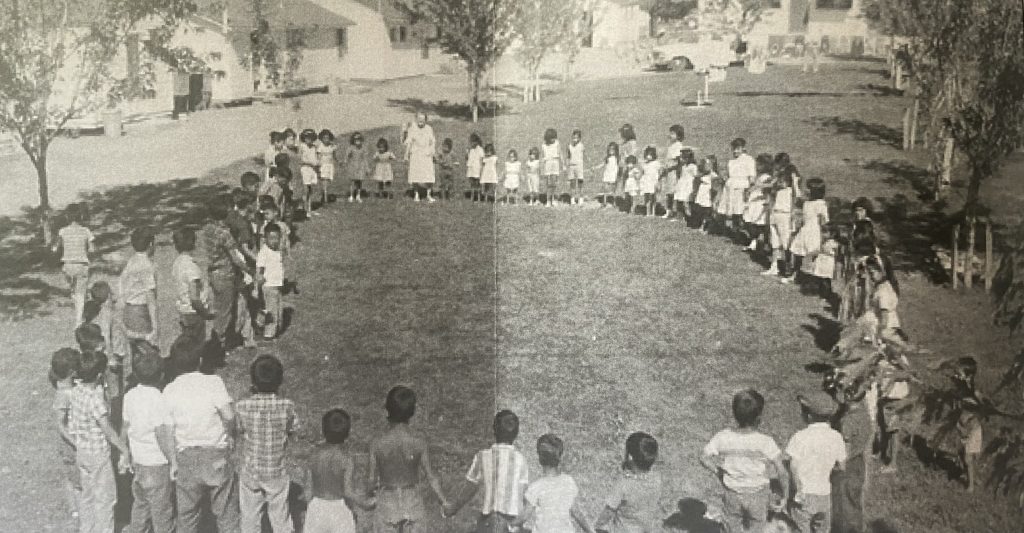

Because not all the farmworkers had their own cars, and because they worked long days, having a store at the camp was important. The store could extend credit for a week, until payday, which was also helpful. One pay phone on the wall served the entire camp. When it rang, which was often, whoever passed by would pick it up and then search the camp for the intended recipient. Most of the cabins had no plumbing, so water was hauled in buckets from a faucet. Showers and toilets were in central buildings. Trees shaded a lawn with play equipment for children.

Women had to work in the fields at the same time they were taking care of kids. A 1961 report said that the camp contained 58 cabins, which could house about 400 individuals with about 200 workers. Do the math: this works out to a family of 6 or 7 in each cabin. In that family there would be 3 or 4 workers, i.e., mother, father, and one of two of the oldest kids. The younger children had to go to the fields with their parents and older siblings. The smallest children were hard to watch because they were shorter than the sugar beet plants! Women got up early to make breakfast and pack lunches, and stayed up late to cook, clean, and do laundry. Eventually Armando Santos was hired as camp janitor, and since he was around all day, mothers would leave their children with him. He would go about his repair and cleaning duties with a crowd of 20 children following him.

Farm Work

The actual farm work was hard, and camp residents prided themselves on being able to give a good day’s work to whoever hired them. The types of crops varied over the years, and gradually mechanization, chemicals, and better seeds changed the work. During World War Il, spring work was in lettuce and peas. In the 1950s, strawberries grown on the Oregon Slope had to be dug up, separated, and replanted every April.

Sugar beets in spring needed weeding and thinning. The beet seed naturally is compound, so that each seed sent up several plants, which had to be pulled out by hand, what the farmers referred to as “finger thinning.” For that work a very short hoe was used, requiring the worker to stoop all day long. Eventually, ag scientists figured out how to “segment” the seed so that one seed produced one plant, and finally in the 1960s hoes lengthened.

Potato and beet harvests were laborious before about 1960. Potatoes were plowed up and workers walked the rows filling burlap sacks. Humongous sugar beets had to be picked up individually and thrown onto trucks. Onion harvest took less strength so children could help, but the tops were cut off with a special sharp, curved knife, which was risky. Long after the beet and potato harvests were mechanized, onion work continued to be done by hand.

Having A Little Fun

Mexican movies played at the Star Theater, and drew audience members from as far away as Ontario and Nyssa. Camp residents also went to see the American films – romance, horror, action. The parks downtown were a big draw, and in summer hundreds of people would relax on the lawns. In the 1980s the Lions built a small park in front of the Labor Camp, where people played volleyball. El Ranchito at various times housed a market, a bakery, a music store, a bar, pool tables, video games, and Mexican TV on satellite, providing a place for people to come in out of the sun and visit with each other.

The Long Sixties

The 1960s and their aftermath changed most things, some for better and some for worse, and of course had an effect on the Labor Camp. Fiestas throughout the Western Treasure Valley, including one in Weiser in 1970, proudly and publicly celebrated Mexican culture. In 1969, the Weiser Labor Pool reincorporated. The purposes of the organization, which had been all about providing labor for farmers, now included providing economic opportunity for agricultural workers, educational opportunity for children, and good housing.

Last Decades

During the 1970s and 1980s, people who had been moving around to do seasonal work began to find ways to settle in one place, even if they continued to do farm work. Mechanization and chemicals decreased (though didn’t eliminate) the need for hand work in the fields. Many former Labor Camp residents settled in Weiser itself. The newer arrivals at the camp were more diverse, many arranging their papers and coming from central Mexico rather than Texas. Laws restricted child labor, mandated porta potties in the fields (1981) and included farm workers under workers’ compensation protection (1996). In the 1990s, some rooms at the camp were built for year-round occupancy, with running water and heaters. In 1978, Mike Heredia retired, and passed away in 1991.

Meanwhile, the Latino/Hispanic share of Weiser’s permanent population increased, from 16.7% in 1990, to 22.9% in 2000, and 26.1% in 2010. A community study in 2002 opined that the camp needed to be “refurbished and salvaged.” In April 2004, the Weiser Labor Pool sold the camp to Haun Onion Packing. The onion company gave away the cabins to local people, many of whom took a particular cabin that they had lived in, to keep as a souvenir.

Julia Soliz and her daughter Betty, who still live next door, said they were surprised, but they’re philosophical, and were very willing to be interviewed for the project that produced this brochure. Julia still has the pay phone that used to adorn the wall of the store.